The dangers of user content

One major challenge modern web services face is how to safely incorporate user content. Naive use of potentially malicious content can leave the service and its visitors vulnerable to attack. Many of these attacks work by code injection, in which improperly handled content is used in an unsafe way. For example, in cross-site scripting (XSS), malicious content is injected into web pages served to users of the web service. This can allow an attacker to bypass the same-origin policy, steal credentials of other users visiting the site, and much more.

In order to prevent these types of attacks, the developers of a service must make sure that all untrusted (potentially malicious) content is sanitized before it is used in an unsafe way. Unfortunately, any mistake could leave a gap that an attacker could use to exploit the service. Trying to find and close all of these gaps, while avoiding the introduction of new ones, can seem like a game of Whac-A-Mole, especially in systems originally developed without following industry best practices.

Tell me before I make a mistake!

Taking a step back, we see that the general problem is that when data is used in a dangerous operation the system has no way to know whether this data is safe to use or not. It's up to the developers to make sure only safe (sanitized) data makes it this far - and to never make a mistake! But there is another way to make sure only safe data is used in dangerous operations...

Information flow is a way to reason about how data flows through a system. Taint checking can provide a dynamic system that approximates the verification from full information flow analysis. In systems that provide taint checking, data from an untrusted source is marked as "tainted" in metadata associated with the data. While we support more sophisticated schemes, let's simplify the discussion by assuming there is only a single bit of metadata for each data value, indicating either "tainted" or "untainted." Tainted data can only become untainted by passing through the appropriate sanitization routine, ensuring it is safe for use.

This metadata accompanies the data itself as it passes through the system, such as from one variable to another.

When data is passed to a potentially dangerous operation (e.g., eval), this tracking system can inspect the metadata on the data to determine if the value is "tainted."

If so, then the system knows that this is (or at least could be) unsanitized data from an untrusted source and should not be allowed to be used in this dangerous operation.

There are many dynamic information flow tracking systems that provide taint checking. Perl and Ruby both include taint modes, and third-party systems exist for other languages, such as Java (PDF link) and PHP. This seems perfect for preventing cross-site scripting, SQL-injection, and many other attacks, so why isn't it widely used in web services?

Limitations of information flow tracking implementations

Unfortunately, most information flow tracking systems only work for a single application at a time. For example, Perl's taint mode only maintains and propagates this taint metadata on data as it flows through the Perl program. The problem is that most web services include not only a web application, but also a database. All the metadata Perl's taint mode tracks is lost when sending data across the application boundaries into the database. Similarly, when data is retrieved from the database Perl's taint mode has no idea how it should be marked. The only two options Perl provides for this is to:

- treat everything from the database as tainted, or

- treat everything from the database as untainted

Obviously, neither will provide satisfactory results for most web services.

Other single-application information flow tracking systems have the same drawbacks. And while system-wide information flow tracking systems exist, these generally lack the necessary granularity and support of database semantics to provide the precision necessary to protect against common web attacks.

What can we do?

DBTaint enables cross-application information flow tracking via databases

At UC Davis, I led a project with the goal of empowering administrators of web services to use existing single-application information flow tracking systems in multi-application web services. Since we enable taint checking from applications into databases, through database operations, and back into the application, we named this project DBTaint. DBTaint was designed and built to meet the following requirements:

- efficient end-to-end taint tracking through applications and databases

- full support of database operations and semantics

- deployment is transparent (requires no changes) to the web application

- requires only SQL-level changes on the database server (uses stock database engine)

Design and implementation

On initialization, DBTaint performs SQL-level changes to the database tables used by the app.

Additionally, DBTaint creates composite-type versions of all of the database data types.

These composite types include the data value as well as the associated metadata (i.e., taint value).

Also, it initializes and overloads the necessary database functions in order to perform taint-value propagation through database operations.

For example, it adds a SUM function that produces an untainted result if and only if all of the values passed to it are untainted, otherwise it returns a result with the highest taint value of all of the input values.

Please see the publications listed below for details on the semantics of the database operations.

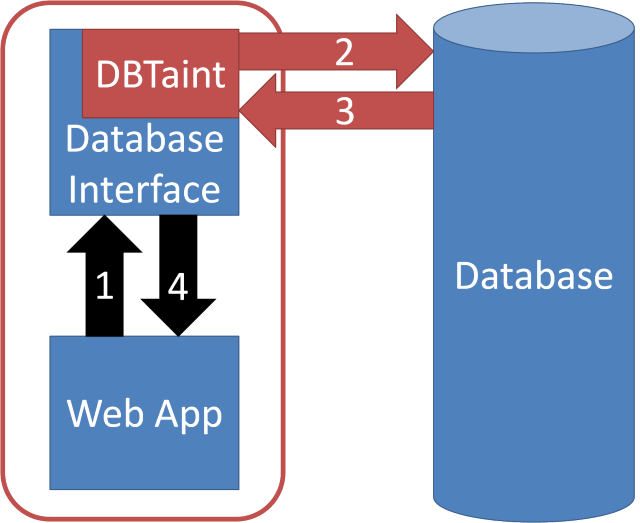

This is a diagram showing a web service running in DBTaint.

In the diagram above, the red rounded rectangle around the Web App indicates the single-application information flow tracking system (e.g., Perl's taint mode). Observe that when a web app communicates with the database via a standard database interface module, this database interface is still running within the same single-application information flow tracking system. The metadata associated with data intended for the database has not yet been lost.

DBTaint provides end-to-end taint tracking transparently to the web application by augmenting the database interface to intercept and automatically rewrite database queries made by the web app. When inserting data, the DBTaint-augmented version of the interface parses the query at run-time, and rewrites it to include the metadata associated with each data value before sending the rewritten query to the database. This metadata is stored and propagated through the database using our composite types and functions. Similarly, when querying for data, our augmented interface will collapse the resulting composite data/metadata pairs it gets from the database into appropriately tainted data values, which it returns to the web application.

A major benefit of this approach is that the web app makes the same queries (and receives the same results) as running without DBTaint, so these changes are completely transparent to the web app. The only difference from the web application's perspective is that the values it receives from the database are tainted appropriately (i.e., more precisely than the all-tainted or all-untainted options available without DBTaint).

Once we have augmented a standard database interface, DBTaint supports any application that uses that standard interface. In our current implementation we augment the Java Database Connectivity (JDBC) interface used by Java programs, and the Database Interface (DBI) module used by Perl programs.

It is a best practice for application developers to use parameterized SQL queries, which makes it easy to determine the taint values of individual data values passed to the database as query parameters. But when a web app creates queries by string concatenation, DBTaint parses the query string and uses character-level taint data (when available) to determine the most precise taint values of each data element in the query.

Using DBTaint for real-world services

Our implementation of DBTaint works with services implemented in Perl and Java that use PostgreSQL databases. We use Perl's taint mode (modified to act as a passive taint-tracking system) and this character-level taint tracking engine for Java (PDF link) to perform the appropriate information flow tracking when running two real-world web services in DBTaint:

- RT (Request Tracker): a popular ticket-tracking system implemented in Perl

- jforum: a powerful discussion board system implemented in Java

Note that these services were not written with DBTaint (or information flow tracking of any kind) in mind, and our approach did not require any code changes to either application.

The performance impact of DBTaint on these systems was relatively low (less than 10-15% overhead) in our evaluation. In additional experiments, we show that we can trade portability for performance by implementing the composite-type metadata propagation database functionality in C rather than in SQL to further reduce the overhead of our approach. Please see our publications for a more detailed discussion of these topics.

Read more in these publications

Parts of this work have been published in the following peer-reviewed publication:

DBTaint: Cross-Application Information Flow Tracking via Databases (paper, slides, poster) USENIX Conference on Web Applications (WebApps). Boston, MA, June 23-24, 2010.

For further elaboration, please see my Ph.D. dissertation:

Protecting Systems from Within:

Application-Level Observation and Control Mechanisms

Dissertation Committee: Hao Chen, Matthew Bishop, Karl Levitt